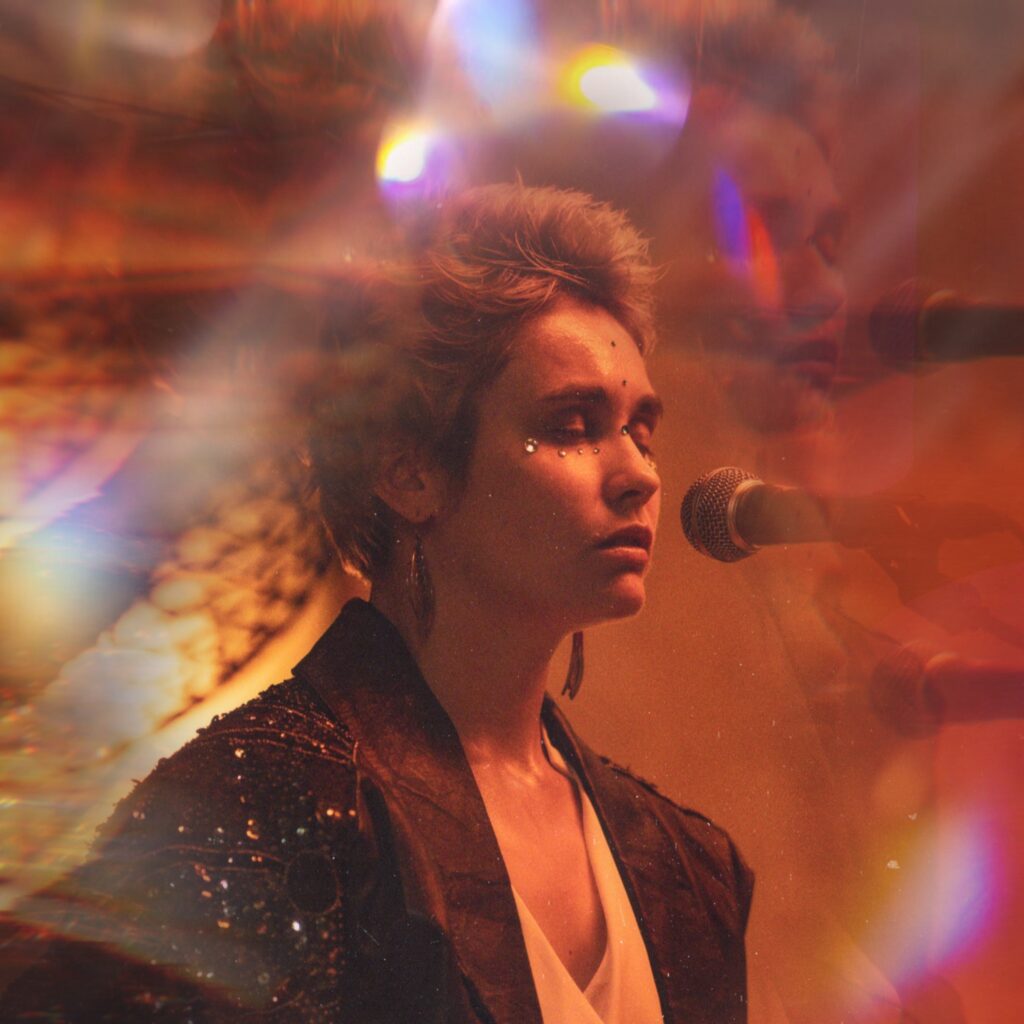

In 2023, I interviewed multidisciplinary artist Daria Pugachova about her Cities of War performance in front of the International Court of Justice in the Hague. Since our interview in the Netherlands, Daria has performed and worked in Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Norway and the US, where she has just completed a four-week residency in Houston, Texas.

One year later, we reconnected to discuss the element of fear in art, changing audience perceptions of art, her experiences with other international refugees, and her own personal transformation as a performative artist.

Let’s start off with a little timeline. Where have you been since you stepped out of your glass box?

I’ve been in many places trying to get out of the box, because I get out of the box physically very quickly, but not mentally and emotionally.

After my residency in Rotterdam, I went to Belgium for a one-week theater workshop called Babel. Then I came back to Bulgaria to take part in a project called WE SEE UKRAINE, which invited four artists from Ukraine, one Bulgarian, and one Croatian to discuss how artists perceive war in Ukraine, and how they’re going through it.

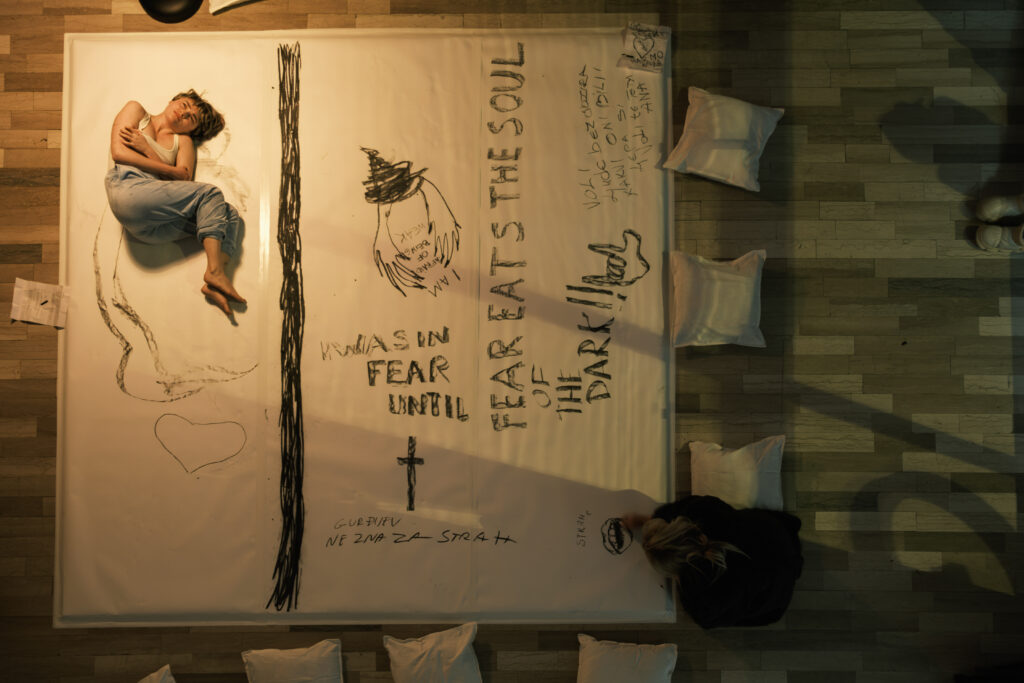

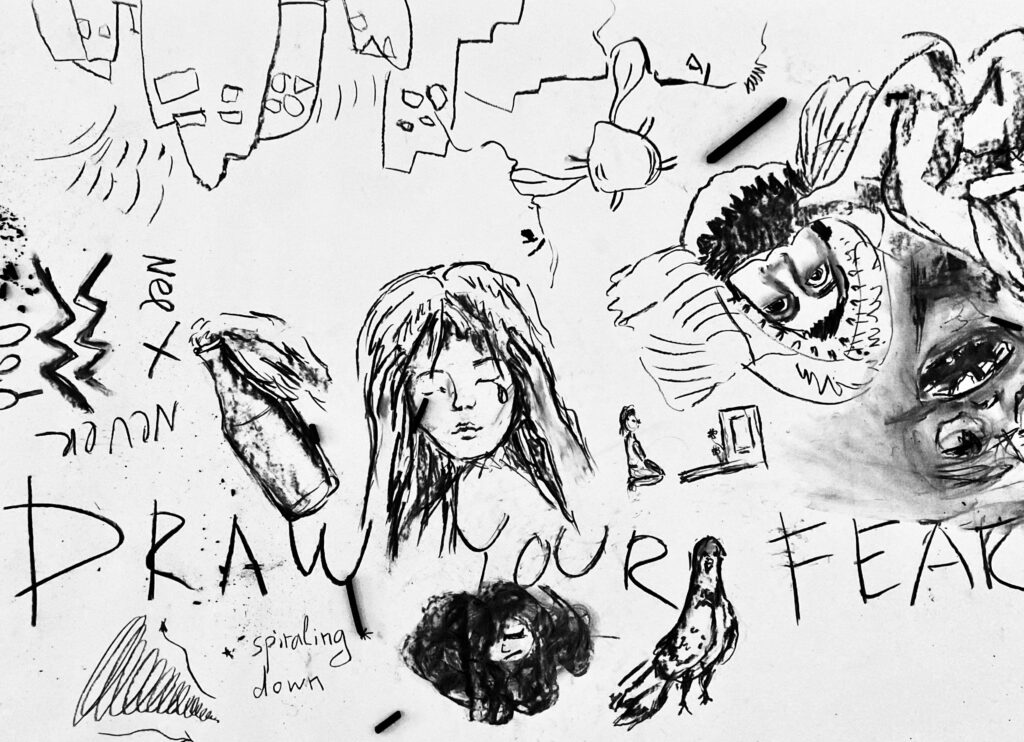

And as part of that project, I performed a piece called Through The Wall – first Plovdiv, then in Zagreb in December [2023], and then in February [2024], in Sofia. I had a huge piece of paper covering the entire room, and I drew a line using coal between me and the audience like an invisible wall. On one side of the line, I performed how my body physically reacts to fear, what I was experiencing in Ukraine during missile attacks.

On the other side the audience explored their fears by drawing them on the paper. The idea was to explore how to pass through this invisible wall that exists between people who have experienced war, and those who haven’t. It was an intimate and challenging performance to go into that state of fear and vulnerability, but we managed.

For this project in Sofia, I had a whole gallery where I exhibited my previous works from other cities. The entire room was like an exploration of fear, and it was paradoxical that despite the topic of fear, I created a very safe space, where I could accept all my emotions. And I felt that was a very grounding experience.

I exhibited CITIES OF WAR in Norway as part of the Inspire Art Award, but also other projects thematizing fear and war. This was challenging work, it was very personal and I felt I could not continue working like this. I needed to go through some emotional healing because I didn’t take the time to process it properly and understand how these performances actually affected me.

When you start working with fear, it opens up a lot of issues from your past. But this is where you should be to process and overcome it. And in general, I had to rethink even my entire approach to art. I had to cancel some projects I was about to go to because I felt I put too much effort, and I wasn’t in the state where I could do it. That forced me to accept myself, and my state of mind and emotions.

In October, I went to the US for a one-month’s residency in Houston as part of the CEC ArtsLink International Fellowship, where I did three performances. Now that my residency is officially over, I am traveling through Boston and New York, taking time for a few weeks to travel and still explore.

That’s actually ties into my next question, namely, how have you seen your own artwork and performances change in the past year? What have you learned to start doing and also stop doing?

I’m learning to put less pressure on myself. I have always wanted to do something big, to raise awareness, to make it large-scale. That was the direction I always wanted to take. But for that, I also need more support, collaboration with organizations, more planning. And in general, I still want to do it, but at the same time, it should be balanced with reality and the care I need to give to myself.

I think I’m learning that. And when I was in the US and I had just one month’s residency, obviously I couldn’t do a big project – I did three small things instead. I learned to just accept invitations I received without knowing what would happen, and I learned to trust other people, and say yes, and just to be open to the process that will come. When you work individually as artists, sometimes you tend to overthink, which puts a lot of pressure on yourself.

You just mentioned working with fear. Do you feel like you can detach your art and your performances from the war? And is that something that you even want to do?

My art is about conflict, but I discovered that I have so many inner conflicts. I wanted to stop the war inside me. I wanted to work on myself, inside and out. And I cannot say that I already stopped it, but through this period, I processed a lot of conflicts, came to peace with some of them, and my art has also shifted.

Can you tell me more about that?

I have started to make more choices in an easier way. For example, in the US, I was invited to substitute for an artist who canceled their participation at the Happening festival (The Orange Show Center for Visionary Art) – two days before the performance!

Usually it would be [impossible for me] to do a performance in just three days. I don’t work like that. I need to think and prepare. But I said yes. And we went to the venue to see what was possible. It was a regular office room, with one black and one white wall. I quickly came up with the idea for this performance, which I titled SPLIT.

On one side of the wall, I asked people to write one bad thing that happened to them last week, on the black side, then on white side, to write one good thing that happened to them in the past week. And in the middle, in the corner, I sat on a horse saddle, wearing a cowboy suit, and my face was covered with an American flag. Then, the third step was to “come and embrace me” – then, they didn’t embrace me as a person but rather embraced a symbol. There is a split in society, and also in individuals.

So in this performance, there are many layers that you can discover, but execution of it was very simple and it was manageable, and then the whole room was covered with these writings with spray paint. People want to express bad feelings, their anger. After writing these things [on the wall], they would come to the middle and embrace both good and bad, like embracing life as duality. Spray paint is a medium to do so. It’s like vandalizing something, and you cannot be very beautiful, you need to have some tools for that. So that worked very well.

What is unity? We tend to think that unity means we are all together as good people doing good things. And this is the ideal. But actually, unity is when you embrace dark and light, when you embrace both good and bad in you and in other people. And this idea of unity came from my inner process.

Do you think that art doesn’t need to be beautiful? How much beauty needs to be in art?

There is one performance by Marina Abramović, who is one of my favorite artists, called “Art must be beautiful. Artists must be beautiful.” In this performance, she brushes her hair and repeats this phrase, but while brushing her hair, she almost turns it into a violent act.

But I think art always has inner beauty, and beauty comes from the meaning the artist puts into this piece. If there is meaning and you implement your meaning and idea in the most essential way, the most simple way, the most communicating way, without overthinking it and just direct action, then it is beauty for me.

I am very interested about your experience as an artist now internationally. How would you describe how the Ukrainian diaspora has changed?

I haven’t had that many encounters with Ukrainians in Houston to say what the difference is between the US and Europe. But in Europe, I think the people whom I met who went during the war, I don’t see a difference. They are all Ukrainian. They have different reasons why they choose one or another country. Some of them had relatives, some of them just felt it would be better for their job, for their children. But Ukrainians, they have the same qualities and values, so I cannot divide them according to the country they choose.

What can you tell me about how you’ve connected with other artists whose countries are also currently at war? Do you find yourself bonding over being an artist in wartime?

Yes, during my residency in Norway for the Inspire Art Award project, I met artists from Congo, Iran/Iraq, Ethiopia and Myanmar – artists who had made refugee or war experiences, and I felt that we shared a lot. We may have different stories and the history of this country and conflict [may be different], but our personal and inner experiences are the same.

For some of us, those experiences were a long time ago. One artist named Gervais Tomadiatunga was a child soldier in Congo. I didn’t know that child soldiers exist. Then later, he became a dancer, and through his dance and performance, he worked on all the trauma and his performance was very powerful. And though it’s a different culture, I understood his stories through the dance because I recognized his trauma.

And there was an artist named Zun May Oo who escaped Myanmar. While studying in Thailand, she made a beautiful piece where she built puppet boxes performing the stories of heroes who overcome evil forces, relating to the fallen protesters in Myanmar. I understood her. I felt so connected to those stories, and I know it all comes from the one feeling.

Ukrainians have suffered from russian propaganda and oppression, demeaning their history and culture. In what ways do you challenge these false narratives through your performances?

Of course, our culture has suffered a lot of oppression from russia – during Soviet times and before. But I think at our core, we always know who we are. I’m Ukrainian and I’m free to be Ukrainian.

The challenge is for Ukrainian artists to be seen and not compete or be compared with russian artists. Our artists and writers are not recognized the way they should be recognized, because we have oppressed by russian culture, which is globally better known. I hope that through my work, I can show who we are, who I am.

For example, I had the chance to give a lecture about my art to students at Brandeis University in Boston. There I could really bring change and awareness, because students are the future. They had very good questions: “What can we do in this time where there is a lot of propaganda and when [the media] isn’t talking so much about Ukraine anymore?” I felt that their questions really made a difference.

In what ways has your audience changed in the past months? How does your audience respond to your performances now, compared to last year?

I think the audience is always the audience…and Ukrainians are Ukrainians [laughs]. I always think about the audience, who they are, what I want to communicate, and their response is always different. Some people like it, some don’t, but there is always a message. And if I do it from that perspective, people feel it. Anywhere: in the United States or in Norway, of course, according to different traditions and mentality and culture, they show it in a different way, people feel it, if only I have this place and space to show this work.

In the US, people are very open and willing to engage. European audiences need more time to [initiate conversation], but once you create a safe space, their responses are there. I am also learning that people are beginning to forget that the war is still going on, and not only in the US. I am tired of answering the question of whether the war in Ukraine is still going on, because it’s not a question.

Dutch audiences’ reactions to Ukrainian art are often focused on the Dutch viewer themselves, or their compliments are focused on Ukrainian artists’ resilience during wartime.

I’m very interested in your views here. What’s the best way that non-Ukrainians can respectfully engage in Ukrainian art? What would you like your audience to tell you? But you already said, the audience is the audience and Ukrainians are Ukrainians.

It’s a good question. When the war started, it was very hard to tolerate these kinds of comments, when people speak without thinking, because you have so much pain. The audience always reacts in different ways. Some people feel guilty, and when people feel guilty, they say stupid things.

But I have also received that feedback, “I’m really inspired by your art,” and I felt like it was profound. And when it was students telling me that, I could really see how my art inspired them to follow their dreams. And I want people to be inspired by my art. I want them to feel that they can also create things and excel in art. Now during my performances I try to focus more on myself and whatever audience response there is, I just try to accept it as it is and concentrate on the performance itself.

I think the audience should just be open to see and feel what is actually there, beyond all the stereotypes or what you read and what you know.

And how can the audience share with you after your performance that they received every emotion that you tried to communicate?

Just share what it was for you honestly. I think probably you cannot receive every emotion and every feeling, but just say how it touched you. If you tell me, “I felt those emotions,” or “I felt your pain,” or “It reminded me of memories in my life.”

If you do it from honesty and really your heart, then it means a lot, whatever it is. It’s not an easy thing because people respond from their minds on what would be something appropriate to say, but when the audience responds by not really sharing what it meant to them, then what does it matter?

Students and children don’t have this filter, so they really share how it was for them. Once after a performance, one young student told me she wasn’t sure what kind of art she wanted to do. But she said “after seeing your work, I want to do performance art, or at least try.” And that was so meaningful.

My last question is what’s your drive? What is your motivation as an artist?

My motivation is create change with the medium of art in the places, spaces, environment that I care about and to inspire other people that they can be themselves. They can be artists, and also we can raise this change together in the most playful and wonderful way. This is the power of unity and freedom through art.

And what’s your motivation as a Ukrainian artist?

My identity as a Ukrainian artist is always part of me. Again, I cannot divide it, or just decide to not be Ukrainian. My work always communicates what Ukraine is, both in and outside of Ukraine, working with Ukrainian people. That’s my background, and that is always there. And I just want to be seen as a Ukrainian artist.

Two days ago I went to the Harvard Museum of Fine Art, where I discovered one artist with Ukrainian roots whom I had never heard about, Louise Nevelson. And I was looking at her work, and I was thinking, “Oh, my God, I studied art in Ukraine and never heard of her.” I think Ukrainian artists are not known even for Ukrainians, but she is famous in the US.

I would love for Ukrainian artists to be known in Ukraine and for outside audiences to recognize them as well. This is something we should work on together: Ukrainian artists, writers, musicians. It’s very important.

This interview was conducted on 15 November, and edited for clarity.

To financially support VATAHA’s work to promote Ukrainian artists like Daria, you can make a tax-deductible contribution here!