On September 27, 2023, a hearing took place in the UN International Court of Justice on the recognition of russia’s war crimes in Ukraine.

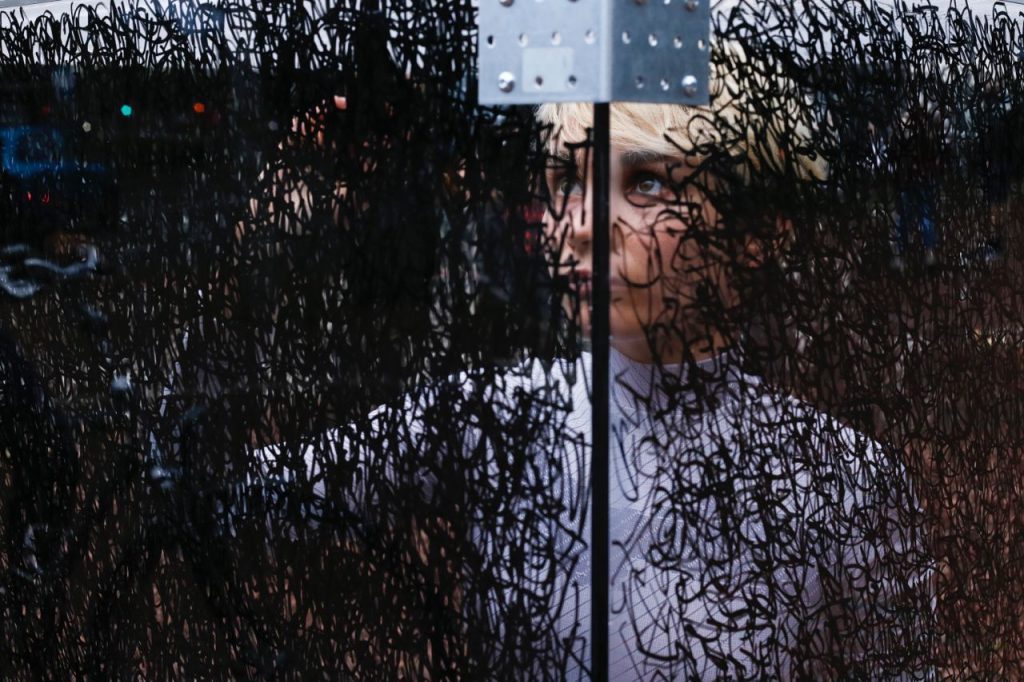

During the hearing, for five full hours, multidisciplinary artist and performer Daria Pugachova put herself in a glass box, and uninterruptedly wrote the words “The War in Ukraine is Still Going On” until the transparent box turned fully black.

Can you tell me a little bit about what VATAHA’s role was in supporting you in this demonstration?

First of all, this was not a demonstration. It’s important to say that it was a performance, and these are just the kinds of performances I do.

I am an artist with a residency at the Goethe Institute in Rotterdam, supported by the INSPIRE research project. For this type of performance, I needed a special permission from the municipality to do it in this space. So I wrote to the Ukrainian Embassy to ask how I could get permission and I was put in touch with [VATAHA co-founder] Uliana Bun. VATAHA helped me get the permission on time.

Photo credit: Milton Verseput

What motivated you to do this performance?

Since the war started in Ukraine, in general, I’ve worked only on the topic of trauma and war and creating awareness of what’s happening in Ukraine to people outside. I came to Rotterdam in the middle of August to participate in a residency that is also dedicated to war, and how artists could work with that topic.

Also, Ukrainians are currently going through this feeling of loss, an inner process. This loss is becoming more and more visible; even when I randomly meet Ukrainians in Rotterdam at events, I immediately feel a connection, a collective feeling.

And one day, I started to write “The War in Ukraine is Still Going On” multiple times in my notebook until the page turned black. That’s how I got the idea to bring this idea to the city so people could see how we feel in our homes in Ukraine, and how we have experienced this loss when we go outside. The war never ends for us, we are not in safety. In contradiction to such a peaceful environment like the Netherlands, we feel this war happening inside us and this is actually our reality.

Photo credit: Milton Verseput

Meanwhile, I was researching what’s happening here in the Netherlands because I always try to connect my performances to local contexts. It just happened that at this time there was this hearing, and that was the moment I decided to do a performance at the Peace Palace during this court procedure because I wanted to connect with people who take decisions like diplomats and ambassadors and make our loss and our struggle visible through art.

I believe that photography and news can sometimes get to be too much and doesn’t always reach the feelings of people because it’s very hard to see all these pictures. Through art, you can get directly to their hearts.

“The War in Ukraine Is Still Ongoing”: Why did you choose this statement and not something else?

It was just something that I felt. I decided to start to write it in my notebook, so it came from my heart. We have been living through war already for 583 days [at the time of this interview]. Here in Rotterdam, it is so beautiful, but the war in Ukraine is still going on.

How does it relate to the public’s war fatigue?

Yes, that’s also the reason for this statement. Countries are getting tired and people in general just don’t want to talk or hear about war anymore. It’s tiring to be focused on Ukraine and some of them say, we just want this to end. And that’s okay. I can understand that they are tired. But we cannot get tired in Ukraine.

Photo credit: Milton Verseput

How do you feel about the fact that your performance was for a hearing to even determine whether the International Court of Justice (ICJ) is eligible to rule on russia’s war crimes?

Its’s a very, very slow process that has been ongoing for the past year. Of course Ukraine provided evidence and asked the court to take charge, and russia countered saying that the ICJ not even in a position to make such decisions.

I did what I needed to do in that moment and I showed transformation within just five hours. It shows that you can create a totally different reality in five hours and change everything around you. I cannot influence the court, but I can influence people who take decisions just to get to their emotions, to have them feel what it is like to experience war and genocide in Ukraine. That’s something that is missing in all of those procedures. Of course, it’s a long, official process, but our reality with the war, the killing and the loss, it’s very different. It happens very quickly every day.

Have you ever seen that kind of performance in a cube before? How did you come up with the idea of performing a cube?

The cube is a sacral geometry form, it is very symbolic. Throughout the history of art, it’s present in many works, for example, Malevich’s Black Square. Also, the cube is a very simple structure and symbolizes home.

Your performance space, the glass box, was closed from the top. How did you prepare for that?

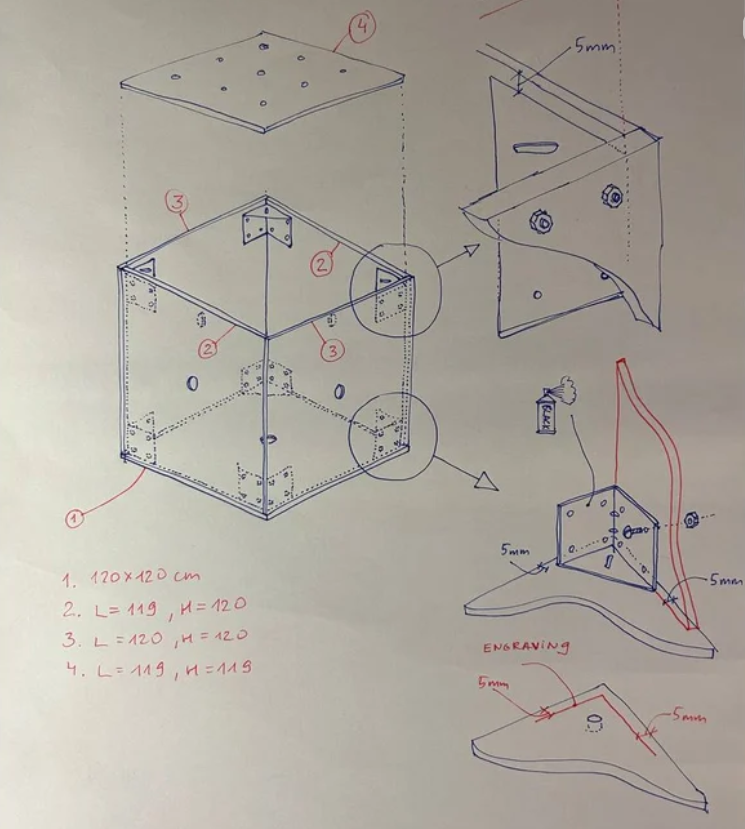

The main preparation for me was actually to create this cube. I prepared everything in maybe less than one month because I am only here in Rotterdam for a short time. Also, the procedure of genocide was happening that week. So I had to finish before September 27th.

It was very, very hard to manage everything on time. A Rotterdam-based architect named Michael Hadjistyllis helped me design the cube and to create ventilation holes so I could breathe.

Drawing by: Eugene Bogira

But I decided to build the cube in Ukraine because it was shorter to have it constructed there and deliver here than to make it in Rotterdam. The delivery was stressful because of its weight and it was hard to find a driver to deliver it. And we also only got the municipality permission for the performance a week before the 27th. Up until then, I was organizing everything without knowing if I had permission.

Everything came together in the last moment. And I didn’t even have any time to physically prepare myself but was confident because I have done physical performances before and I know that you cannot actually prepare for them.

Performance is something that only happens in one moment of time. It all comes together. You cannot rehearse it. I practiced writing for one hour on paper so I knew that I could fill this box with writing, but for the real performance you need that moment: the right place, the people, the purpose.

Tell me a bit about the rest of the physical preparation.

In terms of my outfit, I have already worked with bodysuits in my previous work. And I knew I wanted to have another bodysuit, something light-colored inside the black cube. For me, it also represents that despite the war, we still have our hope for freedom and our love for our country which is something that you cannot kill.

It wasn’t enough for the suit to be white. I needed a special pattern. I saw an exhibition of local artists, Aliki van der Kruijs and Jos Klarenbeek. They explore data from the sea and its wave, and weave textile patterns with machines from their data. At that exhibition, I saw the sea-inspired textile patterns appear as camouflage and I was amazed by that. This gave me a new perspective on camouflage – camouflage made by the sea.

I just reached out to Aliki and Jos to collaborate on this performance. We made the suit using their camouflage patterns. As an artist, I’m also fighting for peace and for freedom of Ukraine. The bodysuit became a uniform, but it’s a peaceful uniform.

I also had a lot of markers because one was not enough. I needed to use non-alcoholic pens because otherwise after five hours I would have been drunk from their fumes.

Photo credit: Milton Verseput

Once you finally got into the box, what was going on with you physically, but also mentally and emotionally?

It was painful to do it for five hours without a break. I knew that I couldn’t take a break because when you do one motion constantly, but then take a break, you lose all your energy. Maybe from the outside, you could not even notice because I was writing constantly.

Also, I could feel that we didn’t make enough holes for ventilation so it became quite hot inside. The top of the box started condensing with water. I didn’t write on the top until the end of the performance. It turned out quite beautifully because when I did start writing on the top, it was like writing on a mirror after a shower. It was beautiful because by then the box was entirely black but from the top you could still see the sky. So this evoked hope, again, and freedom.

And mentally I tried to be fully empty of thoughts, just to focus on my action and this message. So I was just repeating this phrase. This state of mind helped me to be very focused and to be able to finish this work. I couldn’t have any distraction. Taking note of people on the outside would have turned my attention away from what I actually needed to do. Reality from the inside of the cube was quite different from what happened on the outside. I was not connected to people and I was really in the box.

Photo credit: Hosein Danesh

Did people interact with you or try to get your attention?

There was a lot of interaction, both from people just passing by but also from Ukrainians who specifically came to support me. A lot of people tried to look inside and just walked around. Diplomats walked by and I know that russian diplomats and ambassadors were observing my performance from a distance.

I remember one Ukrainian woman specifically asked me, “Young girl what are you doing there?” I could hear her of course, and people had a lot of questions. But I didn’t interact with anyone. Only once when my cameraman asked me if I’m okay, and I had forgotten to tell him that I wasn’t going to talk so I told him “I’m okay but I am not talking” then he didn’t bother me again. Other people, like my friends, explained instead.

I also know that some Syrian refugees came and asked what’s happening and whether I had eaten and drunk something. They left and came back with a hamburger that they wanted to give me. Uliana [Bun] then explained my performance to them.

Photo credit: Milton Verseput

Did you finish when the hearing was over, or when the box was black?

My intention was to do it for five hours. The hearing took place from 3-6PM, so I decided to start and hour before and end an hour after so the people exiting the hearing could see the cube’s transformation.

How did it feel when you finished, when you wrote the last sentence and you put your pen down? What happened next?

I wrote my last sentence on the side and then I wrote the same on the misty glass lid. And then I just lied down and looked at the sky for five minutes. I closed my eyes and tried to feel my energy and acknowledged that I was finished. I knew I could take this time for myself to actually focus on my body and what I felt and on what I was going through.

So it was a moment of peace for me. I also knew that once I would leave this box, then I would connect with people so then I would break this isolation barrier. When I heard the church bells ring, I knew it was 7PM, so I got up and people helped me remove the lid because it was quite heavy.

Photo credit: Hosein Danesh

I was standing there for a few minutes without moving or talking, just taking in this new reality. People were standing around and looking at me, waiting for me to say something but the moment I started to talk I began to cry. All those emotions and all these statements that I was writing for five hours were also imprinted in myself and my emotions just came out.

I then started talking to the people who came to watch and thanked everyone for supporting me. I was grateful to everyone who made the performance happen.

Where is the box now?

The box is now in the Rotterdam Goethe Institute. I plan to exhibit it in museums, for example in an exhibition in Nitja Centre for Contemporary Art, Oslo next year. I would like to show it at as many places as possible. I will experiment with the timing and the size of the box, so I can do this performance longer and with a smaller size I can fully cover the top. So there are options. This box is kind of iconic now.

Photo credit: Hosein Danesh

What’s next for you?

I will probably go back to Sofia, Bulgaria, where I used to live. But in ten days, I am taking part in a workshop in Brussels, and next month, I will have performances in Bulgaria and Croatia. It will again be about evoking emotions in people from outside of Ukraine. But these upcoming performances will not have a political purpose, instead, in a more intimate performance, focus on understanding what it means to experience war.

What would you say to artists who are inspired by your performance and who are thinking about following your footsteps? Confining themselves to a small space to share a strong, political message?

Don’t be afraid of your ideas. Just follow what feels right. Of course, there will be a lot of struggles. But if your idea is strong and you have faith and enough patience, you can make it, even if it seems impossible in the beginning. Just start doing it and the support will come to you.

This interview was edited for clarity.

You can take a look at Daria’s previous performances on her website here, and follow her on Instagram here.